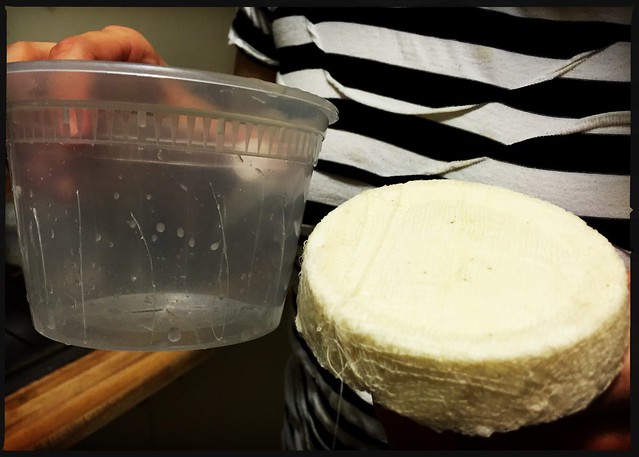

Our homemade brie is successfully growing its furry little coat of mold! And just look at how different they look compared to when I first took the curds out of the forms!

They’ve really flattened out. I didn’t even notice this until I looked back at that old post!

However, I did hit a bit of a snag, which I think I should warn everybody about. I was following instructions from a zine that said, “when you see mold, wrap it in cheese paper” so I did just that. The zine then went on to describe all the terrible horrors that await the person who waits too long to wrap their cheese (and showed photos of drying mats tearing the mold off of the surface of the cheese, thereby ruining it). Nowhere did it mention it would be a problem to wrap the cheese too early.

Turns out this was slightly misleading. I interpreted this to mean, “wrap the cheese as soon as you see even a microscopic hint of mold,” when actually what they meant was “once the cheese is completely covered with a thick blanket of mold.” The problem with covering the cheese with cheese paper as early as I did is that the moisture sitting on the cheese where the paper is touching it will actually inhibit the mold growth (which is ironic, as mold will also fail to form if there’s not enough moisture).

Luckily, I was so excited to see how the mold was coming along that I unwrapped it to take a peek and noticed that the sides were covered with a luxurious coat, whilst the tops and bottoms were patchy-to-completely-bare. Concerned, I looked up a second opinion on brie making, and saw that the consensus was to wait until your brie is completely covered before wrapping it. Whoops! So I unwrapped them and returned them to the casserole dish that had previously been their mold-making home. There, I hoped they would still form the mold all over, as if I hadn’t ever wrapped them in paper.

Luckily, it would appear that they have quickly recovered from this error, as you can see in the photo above (taken about a week after discovering my error). I don’t know what this means for the aging time, to be honest. I suppose I’ll have to feel it out. By the original estimates, they should be ready next week at the earliest, but they are supposed to age for ~4 weeks after getting wrapped so I think this moves things back a bit.

So let this be a warning to all you would-be cheesemongers out there: wait until your brie is completely covered in mold before you wrap it in cheese paper, or meet the same fate! No matter what your zines say.